The nation’s roster of state birds is colorful but not so diverse

(published 6-7-23)

I drive with a cardinal on my license plate. It costs a little more but not as much as a plate that says COWBIRD, which I observed last year during a visit to Champaign-Urbana. If the owner of that car is reading, I’d love to hear your story!

|

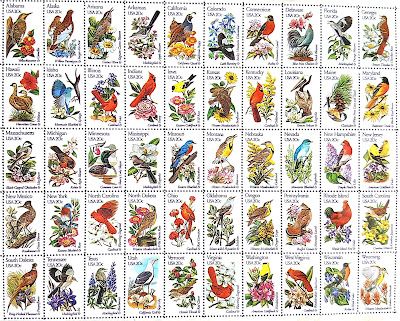

| These state bird and flower stamps, issued in 1982, were highly popular. All 50 stamps are unique, but many states share the same bird. |

Until now I’ve stayed clear of state birds, a hot button for

some birdwatchers. We have some strong opinions on the matter. In fact, if

birders had their way, the current line-up of state birds would look a lot

different.

For starters, the cardinal would not be shared by seven

states, western meadowlark by six, and northern mockingbird by five. Only 20 of

our 50 states have a unique state bird. With so much avian variety to choose

from it seems like we could do better. There are some states where a new state

bird makes so much sense.

One is Michigan. The first thing I’d do if I moved there is purchase

a Kirtland’s warbler license plate, which became an option in 2022.

Michigan’s state bird, however, is the American robin, chosen in 1931. The Kirtland’s Warbler Alliance is out to change that, and there is currently bipartisan support in the Michigan state legislature to adopt the rare warbler as the official state bird. Doing so would recognize the state’s successful efforts to bring Kirtland’s warbler back from the brink of extinction in the 1980s.

Replacing a state bird is a difficult process, achieved only

once before when South Carolina booted the mockingbird in favor of Carolina

wren, in 1948. Michigan might just pull it off, and by doing so would be the

first state to officially recognize a warbler species—and one that is uniquely

tied to the state. Two other states, Connecticut and Wisconsin, would still

have the robin.

Kirtland's Warbler by Christian Goers

There are at least three good reasons why seven states celebrate

the cardinal. It’s common, brightly colored, and non-migratory. In other words,

the bird is accessible. Anybody can see it, everybody knows it.

Kirtland’s warbler passes the color test but finding one takes

effort. Their primary breeding range is a small section of northern Michigan

(lower peninsula), and in the fall and winter they live in the Bahamas. Most

Michiganders will never experience a Kirtland’s warbler unless they seek it

out.

Must a state bird be conspicuous and familiar? Or may other

factors such as local history, conservation success and geographic uniqueness win

the day? Michigan legislators may soon have the answer. Keep an eye on H.B. 6382.

In 2010, some Illinois birders floated the idea of changing

the state bird to red-headed woodpecker. Bob Fisher, president of the Illinois

Ornithological Society at the time, asked a fair question: “Wouldn’t it be nice

if the state bird was more representative of what the state was like when it

was founded?”

“When Illinois was being settled, you could spot the red-headed woodpecker along the creeks and rivers, whereas you would have been hard pressed to find a cardinal,” Fisher added.

Indeed, despite the moniker “northern cardinal,” our familiar

redbird was primarily a southern species in the 1800s. Its northward range

expansion occurred in the last century.

The native roots issue aside, red-headed woodpecker is in

decline and needs conservation. Making it the state bird, birders argued, would

bring it needed attention. Red-headed Woodpecker by Jeff Reiter

Alas, the grass-roots effort earned some publicity before

falling flat. The beloved cardinal was untouchable.

None of the seven cardinal states are considering a change.

But just for fun, the Cornell Lab of Ornithology recently conducted a “thought

experiment” using eBird data to select alternative birds of honor. With eBird, Cornell’s

self-serve database based on millions of citizen-science records, researchers

can estimate the frequency of any bird species in any state. Cornell’s analysis identified a logical bird

for every state, 50 different species.

For Illinois, the eBird choice is indigo bunting, a blue

beauty found in every county during spring and summer. Data show that 6.9% of the

global population breeds here, the third highest of any state.

I especially like eBird’s selection for Indiana, another redbird

state. Cornell said sandhill crane would be a proper choice, given that Indiana

hosts the second most cranes in winter and during spring migration. Birders know

to visit Jasper-Pulaski Fish and Wildlife Area in the late fall to see the

biggest annual crane gathering east of the Mississippi River.

Sandhill crane would be a nice choice for Nebraska, too—a

chance for the Cornhusker state to break out of the western meadowlark cluster.

Finally, a confession: When I dove into this subject, I found

it hard not to be judgmental. I was looking for mismatches and undeserving

state birds. That was a mistake.

The eBird exercise showed that better choices may exist. But the

current roster of state birds needn’t be viewed with disdain. All are worthy,

all chosen for a reason.

A few even come with a good story. I learned, for example, that

Utah picked “sea gull” because it saved the state from swarms of crop-damaging

crickets in 1848. More than 100 years later, Utah clarified its choice as

California gull, a species found in big numbers around the Great Salt Lake.

I do wish that every state had its own bird. Only 20 can make

that claim, and hopefully Michigan will make it 21. Talk about a good story: the

case for Kirtland’s warbler is too compelling to ignore. If Michigan gets it

done, other states might take a harder look at their own state bird choices.

Copyright 2023 by Jeff Reiter. All rights reserved.