|

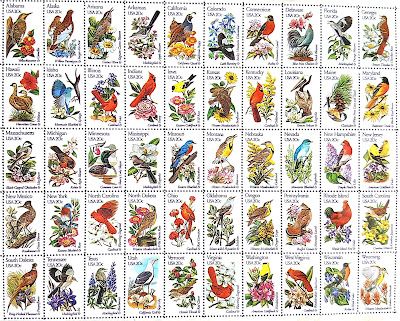

| “Feathered Friends,” by emerging author and artist Madelyn Lee, contains fun facts about birds in backyards and around the world. (courtesy Early Light Press LLC) |

In August, an answer to that question arrived in a carefully

wrapped package from Virginia. Inside was “Feathered Friends,” a children’s picture

book from first-time author and illustrator Madelyn A. Lee, age 18.

I don’t receive review books very often, and this one was

unlike the others—an oversized field guide for toddlers. The book’s 32 pages

feature 17 birds, and how prescient that one of them is American flamingo, a

species that crashed Virginia (and 10 other states) a month after the book’s publication.

Copies of Madelyn’s book flew off the table at a Barnes

& Noble book signing in Williamsburg, just before she went off to begin

studies at the Savannah College of Art and Design.

No, I did not add “Feathered Friends” to my Goodreads list. But

I’m keeping that option in my hip pocket. A book is a book, right?

Yes, and potentially much more. The surprise arrival of “Feathered

Friends” started me thinking about books for kids and their power to influence

how we feel about birds and nature. Young minds remember stuff; early exposure

to birds and conservation themes can only be good. Worked for me!

|

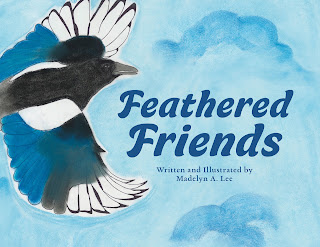

| The inspiring Monty and Rose books, this one and its sequel, are about birds and birders beating the odds on a busy Chicago beach. (courtesy plovermother.com) |

You probably know about Monty and Rose, the piping plover pair that captivated Chicagoans by raising a family on Montrose Beach in 2019. The endangered species hadn’t nested here in more than 70 years.

Monty and Rose chose a tough neighborhood to call home. It

took a small army of dedicated volunteers to protect them during their time on

the busy strand. The general of that army was Tamima Itani, an Evanston

resident who serves as lead volunteer coordinator for Chicago Piping Plovers, a

collaboration between Chicago Bird Alliance, Chicago Ornithological Society and

Illinois Ornithological Society.

Tamima is the go-to source for information about Monty and

Rose and their extended family. Nobody knows them better and turns out she has

a gift for putting good stories into words.

Tamima’s two children’s books, “Monty and Rose Nest at

Montrose” and “Monty and Rose Return to Montrose,” will leave an impression, I

promise. They are adorable but also informative and real. The illustrations by

Anna-Maria Crum are terrific.

|

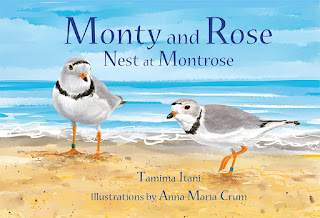

| “The Christmas Owl,” successful on so many levels, shines a light on the important role of wildlife rescue centers. (courtesy Little, Brown and Company) |

On the cuteness scale, a piping plover is hard to beat, especially

a downy chick on toothpick legs. Northern saw-whet owl is another heart melter.

Do you remember Rockefeller? She’s the saw-whet who was discovered trapped in New York’s Rockefeller Center Christmas tree in 2020. Like Monty and Rose, “Rocky” became national news—a feel-good story when our Covid-stricken nation really needed one.

I wasn’t aware of “The Christmas Owl” until my wife purchased

a copy in September. It’s a special book, and a New York Times bestseller at

that. I like it because it highlights the important role of wildlife

rehabilitators, in this case Ravensbeard Wildlife Center in Saugerties, N.Y.,

which came to Rocky’s rescue. The center helped her recover and then released

her back into the wild.

One of the book’s coauthors, Ellen Kalish, founded

Ravensbeard in 2000. You can watch her set Rocky free in a short video posted

on the center’s website. Have a tissue ready. The site offers a line of Rocky

merch, too. The famous little owl with the saucer eyes is a fundraising dynamo!

|

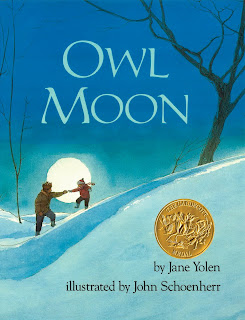

| “Owl Moon” won the 1988 Caldecott Medal for its illustrations and remains in print, available in nine languages. (courtesy Penguin Random House LLC) |

Yolen has more than 400 children’s books to her credit. She considers “Owl Moon” her best. If you are not familiar, do check it out.

Next month is the Christmas Bird Count, an all-day event

that begins with pre-dawn owling. I always think of “Owl Moon” when I’m out

there in the cold and dark, not knowing if the effort will be rewarded. As Yolen

writes, “When you go owling you don’t need words or warm or anything but hope.”

Copyright 2023 by Jeff Reiter. All rights reserved.